Imagine telling Henry VIII that if he married Anne Boleyn he would be dead a few months later… Can’t picture it? Neither can I. After all, he was notorious for simply beheading people who said that. But what if those words came from a nun? A nun who prophesied and predicted, claiming that she had visions and spoke the word of God. Would she be safe from his wrath? Turns out – no. Apparently being a nun and predicting the death of the king still got you into trouble. Intrigued? Read below for the story of Elizabeth Barton; the Holy Maid of Kent.

Sadly, not a lot is known about the early life of Elizabeth Barton, we know very little about her childhood or her family, but it is believed that she probably received little to no formal education and was most likely illiterate. We do know that by the age of 19 she was working as a servant in the house of Thomas Cobb, the farm manager to Archbishop Warham. This is where things start to get interesting.

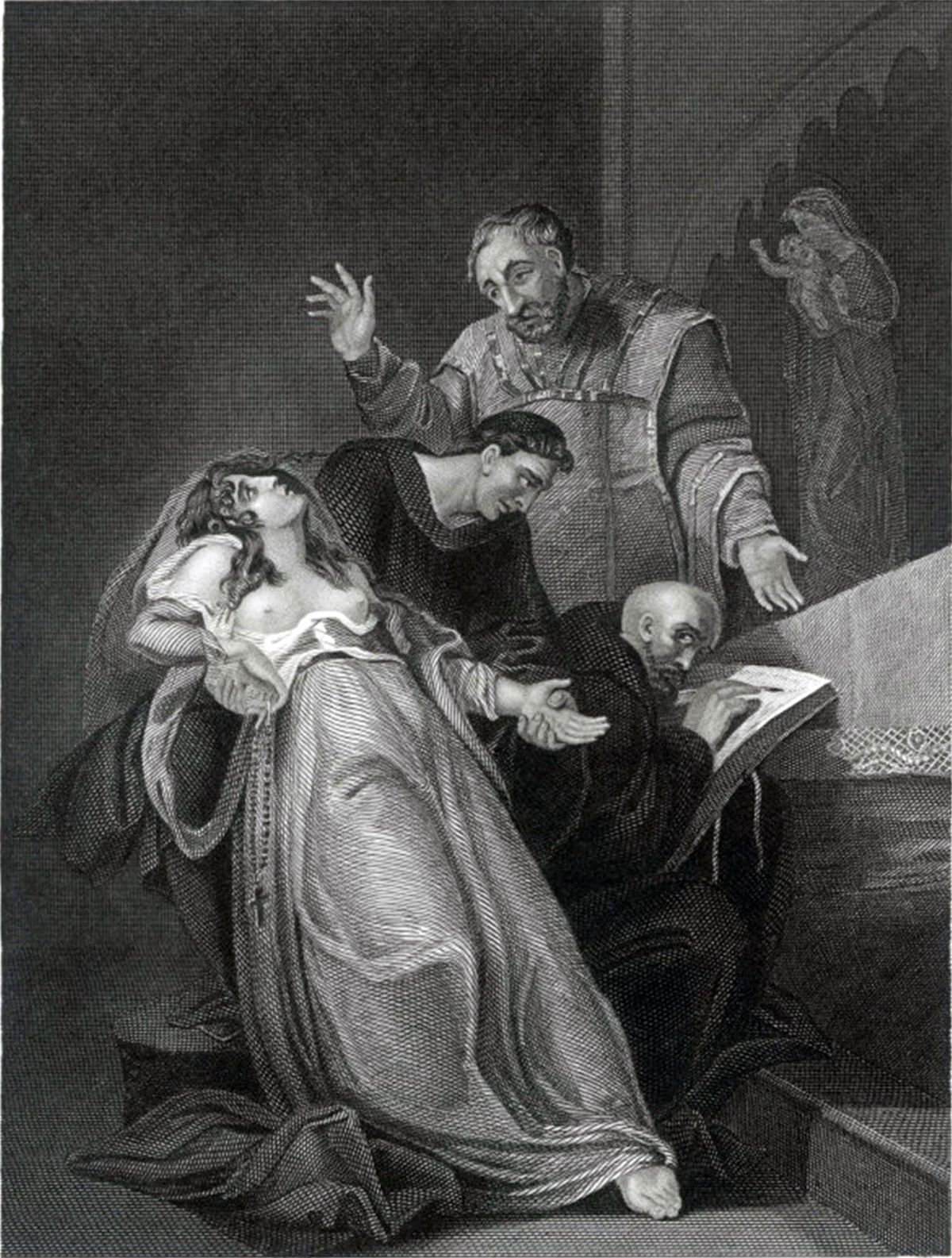

Whilst working one day, Elizabeth became severely ill and started having fits and whatever illness it was, it prevented her from eating and drinking until eventually she fell into some sort of trance – weird right? During this trance, she began to make predictions, predicting that a sickly child would die. She also experienced visions of heaven and spoke about the ten commandments and the seven deadly sins. Eventually her predictions began to gain traction in the local community and she became a bit of a local celebrity but her holy abilities needed investigation. The parish priest therefore travelled to Canterbury to inform Archbishop Warham about her strange and divinely inspired abilities.

Warham conducted an investigation into Barton’s abilities and following her interrogation, Elizabeth predicted the end to her sickness, stating that she would be cured by God in the village of Court-at-Street in Kent. In 1526 it is reported that she travelled to Court-at-Street and was cured – conveniently- in front of three thousand spectators. Elizabeth then claimed that it was divine will that she become a nun and that a monk named Father Bocking should be her spiritual advisor. God really did have plans for her it seemed!

Following the dramatic event at Court-at- Street, Elizabeth entered the Benedictine priory of St Sepulchre in Canterbury and by the summer of 1527 she had taken her vows to become a nun. Father Bocking –*gasp*- was appointed as her confessor and advisor, and he dutifully sent accounts of her revelations to Henry VIII. Henry passed these documents to Thomas More, wanting his expertise on her predictions; her visions were now under the scrutiny of Henry VIII, something she would later regret.

Elizabeth’s reputation had spread by the time she had joined the convent and as such, people would travel to see her to gain her insight into their lives. They would implore her to beg for God’s intervention with sickly loved ones and ask her to commune with the dead. When Archbishop Warham visited her he found himself impressed. He even wrote to Cardinal Wolsey commending Elizabeth to him and indicated that she wanted to meet with the cardinal. Wolsey interviewed her twice that we know of and it is believed that it was his insistence which gained her audience with the king. Elizabeth spoke to Henry about numerous revelations and visions and it is believed she held royal favour for a time. But soon things would turn very sour.

Between the years 1526 and 1534 Elizabeth Barton’s predictions and prophecies became increasingly political and correlated with the religious and political turmoil of the time. Now I think this was mainly due to her spiritual advisor Father Bocking. When Henry VIII began to shift his religious policies, Elizabeth became a fierce opponent and argued that the estates and revenues of the Church and pope should be protected and that those who had heretical thoughts against the Catholic Church should be condemned. Elizabeth continued to spread inflammatory religious ideologies which directly contradicted the will of the king and condemned him for heresy- not the best plan. She then made things much worse when she decided to involve herself in the ‘Great Matter.’ Elizabeth was a staunch defender of Katherine of Aragon and was virulently opposed to Anne Boleyn. Under normal circumstances that wouldn’t be enough to result in imprisonment but Elizabeth took things to a whole new level when she began prophesising – shock. Her prophecies were deliberately inflammatory and provocative and her most incendiary prophecy predicted the death of Henry VIII should he marry Anne Boleyn. Her words were as follows:

“that in case hys Highnes proceded to thaccomplishment of the seid devorce and maried another, that then hys Majestie shulde not be kynge of this Realme by the space of one moneth after, And in the reputacion of God shuld not be kynge one day nor one houre.”

25 Henry VIII, c. 12, Statutes of the Realm, 446

Elizabeth also threatened Archbishop Warham and Cardinal Wolsey with threats that God would punish them should they continue to support the king in his quest for divorce. In October 1532 Barton predicted Henry’s excommunication from the Church in- you guessed it – a ‘divinely inspired vision.’ By the end of 1532, Thomas More decided to speak with her, as he had become increasingly worried about her political predictions. However, Elizabeth Barton had considerable authority in religious and social circles and she had friends in high places including staunch critic of the king; Gertrude Courtenay, Marchioness of Exeter. Katherine of Aragon refused to give her audience, however Barton communicated with Pope Clement VII through translators and ambassadors, commending him for his stance against Henry.

But by 1533 and despite her popularity and connections, Elizabeth was in trouble. Cranmer wrote to St Sepulchre’s requesting that she be brought to him at his manor at Otford. She was questioned and released but then Thomas Cromwell began his investigation – yikes. Following a full investigation, Elizabeth was arrested and placed in the Tower of London and on the 16th of November, she confessed to being treasonous against the king, and a heretic. She was forced to do penance at St Paul’s Cross in London and was publicly denounced with her crimes read out. By March 1534, Barton and Father Bocking were indicted of high treason by act of attainder. The act of attainder demanded that any books or writings by Barton be surrendered with threats of fines and imprisonment. On the 20th of April 1534, Barton was executed. She was hung and then beheaded with her head impaled on London Bridge and her body buried in Greyfriars Church in Newgate Street.

Elizabeth Barton is a fascinating historical figure. Powerful men and peasants alike hung on her every word and she communicated with some of the most interesting people in Tudor History. Her conversations and interactions with Wolsey, Thomas More, the Pope and even Henry VIII indicate just how high she rose in such a short period of time. Her downfall however was her involvement in the political and religious turmoil which was rife during her lifetime and the question has to be asked; was she a pawn in a much larger game? Was she used by the people around her who exaggerated her prophetic visions and celebrity? Just how much of what she said did she believe? And were the words put in her mouth not by God, but by men out to gain power for themselves?

You decide!

P.S. The featured photo is not in Kent but Whorlton Church – quarantine is making it difficult to get new photos!

Bibliography

A Luders and others, eds., Statutes of the realm, 11 vols. in 12, RC (1810–28), vol. 3, pp. 446–51

The correspondence of Sir Thomas More, ed. E. F. Rogers (1947)

E. J. Devereux, ‘Elizabeth Barton and Tudor censorship’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library, 49 (1966–7), 91–106

R. Rex, ‘The execution of the Holy Maid of Kent’, Historical Research, 64 (1991), 216–20

S. L. Jansen, ‘Elizabeth Barton: “the Holy Maid of Kent”’, Dangerous talk and strange behavior: women and popular resistance to the reforms of Henry VIII (1996), 41–56

A. Neame, The Holy Maid of Kent (1971)

D.Watt. Barton, Elizabeth, the Holy Maid of Kent. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004)

Very interesting, it was not a wise move for her to make predictions against the King.

LikeLike